|

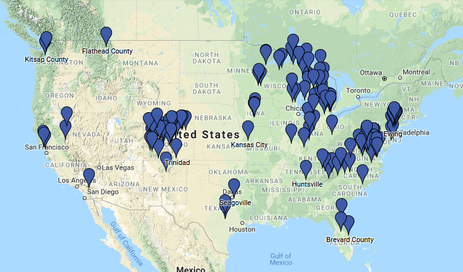

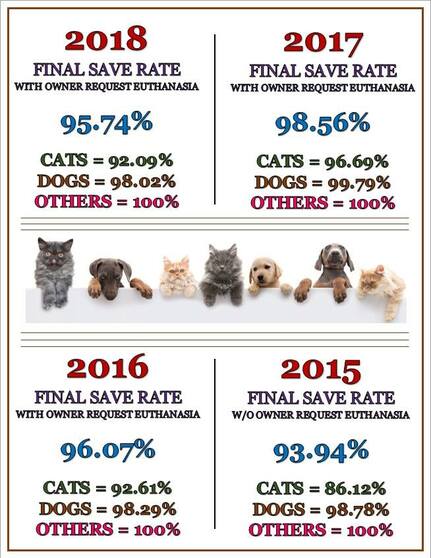

When I became a no kill animal shelter advocate over 10 years ago, you could count the number of no kill communities in the country on two hands. I’m talking about places where all healthy and treatable animals make it out of the municipal and non-profit animal shelters alive in a geographic area. There were plenty of individual no kill shelters across the country, most of which were operated by non-profit organizations which were able to keep all healthy and treatable animals alive by limiting admission. It is easy to say you are no kill when you can also say, “we are not taking more animals because we are full.” Animal shelters operated by municipalities or funded by tax dollars do not have the luxury of limiting admission; they are required to take in animals running at large and exist primarily to serve a public safety function. This means that no kill communities were harder to come by. Times have changed. The number of no kill communities has gone from a handful of locations to hundreds of places across the country. This change has been driven in large part by the no kill movement. We call a movement because it is just that – it is a social movement which is sweeping across the country and which is fueled (at least from my perspective) primarily by advocates in the weeds of animal advocacy who are stepping up and speaking out to bring change to their communities. Some of these people are shelter directors who are taking formerly regressive animal shelters to new places and some of these people are common citizens who are saying, “enough. We are better than this.” No Kill communities are now found across the country from coast to coast in places with very little in common other than a desire to save the lives of shelter animals. In the decade I have been advocating for animal shelter reform in the city where I work, I have heard countless times that no kill sheltering is not possible. A shelter volunteer told me in a recent email exchange that I was “living in a fantasy world” if I thought my local animal shelter could save all healthy and treatable animals. She also said that I was doing a disservice to the animals by using the phrase no kill because I was causing people to falsely believe that all animals in the shelter would make it out alive. What she may not understand is that it is the position of the shelter leadership that no healthy and treatable animals have been destroyed in more than four years. Call me delusional. Fault me for using the phrase no kill all you want. It will not change the fact that my local shelter - and so many other shelters across the country - are saving almost every animal entering the system, proving every day that the no kill model works with commitment to a culture of life-saving. One of the most progressive – if not the most progressive – animal shelters in the country is the Humane Society of Fremont County located in Canon City, Colorado. The HSFC is an open admission animal shelter which serves seven municipalities in Fremont and Custer counties in Colorado, providing both animal control and animal shelter functions. Although the shelter is considered a shining example of no kill philosophies now, things were not always so positive. The organization came under fire in 2013 after complaints filed by former shelter volunteers and a previous employee resulted in two separate state investigations. The Colorado Department of Agriculture, the state agency in charge of regulating animal shelters, cited the Humane Society in Fremont County in June and July 2013 for poor record keeping, for animals being euthanized incorrectly and for lost pets being put down before their owners were given a chance to reclaim them.  All that changed on September 24, 2014, when Doug Rae was hired to be the new shelter director following a national search. Doug had previously managed shelters in Indianapolis, Philadelphia, Maryland and Phoenix and had most recently served as the executive director of the Animal Rescue League of Southern Rhode Island. Doug changed the culture of the shelter on his first day on the job. During his first two weeks he met with dozens of residents, business owners and elected officials. He had one-on-one meetings with every employee and met with past and present volunteers. As Doug wrote in a guest column which appeared in the Daily Record: “I heard sadness, disappointment, hatred and rage. Some folks were brought to tears. Tears for the animals. Though many offered me reasons why the shelter was where it was back then, by the end of our talks, those excuses were now in the rearview mirror never to be heard from again. Instead, we quickly came together and just did it. Well, that's not entirely accurate. Some people not able to embrace the new changes were escorted off the bus at the next stop.” Doug described the change in the shelter as like walking in a flipping a light switch. A shelter which had previously destroyed approximately 50 percent of the animals stopped doing that on the day Doug took over as the director. In his three months, the shelter saved 96 percent of all the animals that came into the building. That number has risen over the last four years. In October 2017, the shelter received the Henry Bergh Achievement Award from the No Kill Advocacy Center and received a proclamation certificate from the President of the Colorado State Senate. Both awards are proudly displayed in the lobby of the shelter. In February of 2018, I approached Doug about doing a video project to highlight the wonderful work being done at his facility. I had hopes of legally clearing a song from a wonderful talent whom I had never worked with before. We got the news in June that we were legally cleared to use “The Other Road” from David Hodges’ CD “The December Sessions, Volume 4.” I was thrilled. It took months for the project to come together, but we were able to finish it recently. Now that the video work is completed, Doug was gracious enough to participate in a Q&A about his facility and about his philosophies. Q: How long have you managed the Humane Society of Fremont County and what can you tell us about your work background that prepared you for the job? A: My first job in animal sheltering was as the Shelter Operations Manager for Maricopa County Animal Care & Control. Back then (2003), this agency took in 62,000 animals a year spread out over three shelters, two locations which I managed. I was in Phoenix for three years. I then moved on to become the Director of Operations at the open admission Harford County Humane Society taking in 6,000 animals a year. This was the first job I was able to have a direct and significant effect on the save rate, since I had the full support of the Executive Director to make any changes that I wanted too. We saved upwards of 97% of the animals. During my time at Harford Humane I was being recruited for jobs across the Country, one in particular, a #2 job in Philadelphia. I refused this job twice but the third request came from Nathan Winograd who asked me to do it “for the movement.” I accepted Nathan’s proposal and became the Chief Operating Officer for Philadelphia Animal Care & Control, taking in 30,000 animals a year. I was only in Philly for about 1 ½ years before we lost the contract to the Philadelphia SPCA after the PACCA Board voted to not put a bid in for the 2009 contract. The highest we got the Philly save rate was a disappointing 78%. As the # 2 in command reporting to the CEO, I take full responsibility for not achieving a higher save rate. But I do wish I had complete control of the Philly agency to do everything that I wanted to do. Our contact with the City expired December 31, 2008. In January 2009 I was named the Executive Director for Indianapolis Animal Care & Control. An agency taking in 18,000 animals a year. Between battling the Union President and a City County Councilor that proposed a City-wide BSL banning Pits [pit bull type dogs] from Indianapolis, a proposal which I publicly would not support, I knew that my time in Indy was at best, limited. Especially after my boss, the Director of Public Safety for the City agreed with me to not publicly support the BSL proposal. But even through the many political battles, my boss supported everything that I was doing, supported my decisions, and battled the Union and the City Councilors along side of me. As soon as my boss resigned due to Parkinson’s disease, his acting replacement (a good friend of the Union President and the BSL councilor) told me to start looking for a job. I refused to resign and instead I was fired in a very public way. I then took a Director job at a shelter in Rhode Island to be close to my ailing mom; who would pass in February 9, 2012. This was the first shelter that was not open admission and the first shelter that I hated working in. After many disagreements with two Board member, I left the agency. I would leave animal welfare due to politics that had nothing to do with saving lives or the animals. Instead, the politics had everything to do with massaging the human ego. Whether it was an elected official, a Union President, a Board member, or others, I had enough. So I turned my back on animal sheltering and went back to retail for almost one year. But I missed working for the animals. And although my wife was adamant that I not take another job in animal welfare, after much discussion, Lynn agreed that I could accept another sheltering job, but only if she was close to family in Colorado. I would soon learn about the Fremont Humane Director opening in COI quickly applied. When a Board member said to me during a face-to-face interview, “Doug you have no idea what the new Director is walking into here.” I simply replied, “Respectfully, I know exactly what the Director is walking into and I know exactly what they need to do.” One last thing, and this is a story in itself, my background prior to entering animal sheltering in 2003 was in retail. I was a National Sales Director for the largest Specialty retailer in the nation and I was a Regional Sales Director for the largest Nutrition Supplement company in the nation. Q: What do you think the most important qualities are in shelter leadership to achieve the no kill model? A: Transparency. An animal shelter Director must be 100% honest in everything that he or she does. And I mean everything. Secondly. A Shelter Director must embrace a quality that puts animals first and treats them as individuals. In other words, the 3 week-old kitten is just as important as the 15 year old lab. The 6 year-old Pitty that people walk past day after day is just as important as the highly adoptable purebred Maltese. The moment someone justifies killing based on reckless opinions, (such as, nobody ever looks at that 6 yr-old Pitty, and because we need space we should put him down because he has had his chance) is the time for that Director to be relieved of his or her duties. Many Board members have little idea how to manage a shelter, what is involved in making life and death decisions, and how to correctly administer shelter finances. I have seen this first hand and I hear it quite frequently from other non-profit Directors. Having worked with some bat-shit crazy Board members over the years, and not that I’m planning on leaving Fremont Humane, but I would never accept a Director position in an animal shelter unless the Board grants me 100% control over day-to-day operations as the Fremont Humane Board did for me during our job interview. One reason why Fremont Humane achieved No-Kill over-night is because the Board allowed me do the job they hired me to do. Too many Board members hire a Shelter Director and then say, “here’s how we want you to do and here’s how we want you to do it.” That is just plain wrong. I read a blog that goes against everything that I just said, saying how the Board (and not the Director) should get the credit for a successful animal shelter. I can’t disagree any more with that articles premise. I know for a fact that I made a Fremont Humane Board member nervous during my interviews; especially when I asked for day-to-day operational control. It’s not easy for a Board to give up control like my current Board did, but Board’s that want 100% control end up micro-managing their director (and the agency) straight into the ground. And not just in animal welfare. I see Boards destroy other non-profits as well. Q: What are some of the most difficult challenges in managing a No Kill animal shelter? A: Fremont Humane receives 2 ½ times the national average for animal intakes and in 2014 our combined per capita was all of $1.07, while the national per capita average is $5.85. One would think that with these two challenges facing you daily, achieving No-Kill would be difficult if not impossible. Well my team proved the naysayers wrong. In our first three months we saved 97% of the animals. In our first year 94%, year two 96%, year 3 99% and last year we saved 96% of 100% of the animals. So any challenge outside of two above is negligible and certainly nothing that could ever get in the way of s shelter achieving No Kill status. Oh sure, there are several challenges a No-Kill shelter faces daily, but none that would ever justify killing an animal. When one of my managers comes to me and starts with, “Doug we have a problem.” I almost always say, “No we don’t…” Q: You’ve had tremendous success keeping animals alive who would have been destroyed in other shelters, particularly dogs who are stressed, anxious or afraid. How do you go about gaining the trust of those dogs and ensuring they do not degrade while in a shelter environment? A: Less than 1/4 of 1% of the dogs that arrived at Fremont Humane over the last 4 years are simply scared. Sure, they may act all sorts of aggressive, but they are scared, plain and simple. Even in an open admission shelter, these types of animals can and should be saved. So while receiving 2 ½ times the national average for intakes, in a shelter that is far too small for our area, and being $4.78 per person below the national average per capita funding level, if Fremont Humane can achieve No-Kill, anyone can. Gaining a dogs trust takes time. Sometimes it just happens, other times it can take weeks, maybe months. Like Louie, a dog that lived in my office for a few months and that didn’t trust a soul. But one day when lying on the floor of my office close to Louie, Louie had a break-through. Louie would soon be adopted. As was Amber and Sugar and so many other dogs that would have been killed on intake in some shelters, but instead they made it to my office where I worked with them at the shelter or in my house Identifying a shelter dog that requires space, and providing that the dog space that he or she needs, whether it be two days or two weeks or two months, is the most important thing we can offer a dog in an animal shelter. My kennel staff does this on a daily basis. I can’t ask for a better kennel staff than I currently have. The reason we are able to save so many “scared’ dogs? My kennel staff and what they do for these types of dogs. When I started at Fremont Humane past kennel staff was always getting bit. Not anymore. I don’t recall the last time a staffer was bitten by a dog in the kennels. Q: What would you say to other shelter directors or to animal shelter staff who are struggling to overcome challenges in order to keep more animals alive? A: Reach out to the community. The same community that Directors blame for the animals coming in their front door, the same community that Directors scold because the shelter “has to kill animals,” that community. And then reach out to rescues. Reach out to sister shelters. Reach out to everyone and anyone you think can help. And then reach down deep and ask yourself, why the hell are you are doing what you do? If you don’t have a good answer, then it’s time to find a new job. If you say you are in this line of work to save lives, but you are killing animals, then call someone that is saving lives and ask for their help. Way back in my first shelter I didn’t have all of the answers, but I did question everything happening around me. Why are we doing that? What’s the reason for this policy? Why would you want to kill that dog? I made a lot of enemies with my mouth in the early days, but it put people on notice. If you sit at your shelter desk and magically think everything will be okay just because you want to save lives, think again. Working animal sheltering is not rocket science, but it’s also not stress-free. Saving lives means many things to many people. To me, it means treating all animals as individuals and doing right by each and every animal that comes into your shelter. The naysayers can nay and say all they want. The truth is that no kill sheltering isn’t just possible. It is a higher calling and it is happening all around us in places like Fremont County, Colorado. The public did not change and suddenly become more responsible. The number of animals in the community did not change. What changed was the shelter leadership, making all the difference in the world to the community, the shelter employees and the animals in the facility. A time will come when all animal shelters are no kill facilities. How long it takes us to get to that point in our society is up to all of us. We hope you enjoy the video. Huge thanks to Grammy award winning artist, writer and producer David Hodges and the management team at Milk & Honey Music (Lucas Keller and Nic Warner) for allowing us to use this wonderful song from Volume 4 of the December Sessions (available on Amazon, iTunes and Spotify.)

1 Comment

2/13/2019 04:33:21 pm

Thank you do very much for this blog about HSFC!!! What a totally awesome story. We remember the poor practices a few years ago and had volunteers reach out for help. To see how far it has come under Doug's leadership is not only amazing but reinforces what is possible.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI am an animal welfare advocate. My goal is to help people understand some basic issues related to companion animals in America. Awareness leads to education leads to action leads to change. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

image courtesy of Terrah Johnson

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed